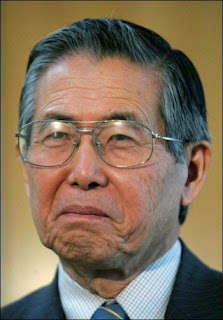

Peru’s ex-president Alberto Fujimori has recently been sentenced to 25 years imprisonment, following a verdict of guilty on four counts of human rights violations.

Peru’s ex-president Alberto Fujimori has recently been sentenced to 25 years imprisonment, following a verdict of guilty on four counts of human rights violations.Alberto Fujimori was on trial for crimes against humanity for allegedly sanctioning the Colina Group paramilitary death squad that killed 25 people in two incidents known as Barrios Altos and La Cantuta. He also faces various other charges for corruption, bribery, illegal phone tapings, and misconduct during his decade-long presidency.

The sentence, and the verdict, are historic in Peru and the hemisphere, as it is the first time a former president has been tried and found guilty of similar charges. Fujimori has also been sentenced to pay compensation of 62,400 soles to the families of each of the 29 victims of the Barrios Altos and La Cantuta cases, and 46,800 soles to each of the kidnap victims Gustavo Gorriti and Samuel Dyer, a total of approximately $614,000.

Fujimori's eldest daughter, Keiko Fujimori, said she “would not hesitate” to grant her father amnesty if she wins the 2011 presidential elections. Human rights activists have rained heavy criticism on Keiko for this suggestion:

“The congresswoman must be reminded that people who have committed crimes against humanity and have violated human rights, crimes for which her father will be condemned, cannot be pardoned or amnestied nor can they receive any type of political, penitentiary or legislative benefit. This is the core of the matter,” said human rights lawyer Carlos Rivera.

“Fujimori has committed crimes of forced disappearances, and this type of crime cannot be pardoned. The Human Rights Court, in its 2001 sentence in the Barrios Altos case, declared that crimes against humanity and violations of human rights cannot be pardoned or amnestied,” Rivera said. “So someone should tell the congresswoman that the pardon will remain a wish because it’s not viable and it’s not legal.”

Fujimori enacted a controversial amnesty law in 1995 that exonerated all military, police and civilians for any human rights violations committed between May 1982 and June 1995 if they were associated to the counterinsurgency war. The law, argued to be necessary for “national reconciliation,” led to the release of those convicted for the La Cantuta and Barrios Altos massacres.

But in September 2001, the Human Rights Court, at the request of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, made an interpretative sentence in which it announced that Fujimori’s Amnesty Laws were without any legal force.

Legislators from different political parties also strongly reacted to Keiko Fujimori’s comments:

“I think that we should evaluate the possibility of writing up a bill that makes it illegal for a person who becomes president to pardon their family members,” said Congressman Juvenal Ordóñez.

Keiko Fujimori is a 32 year-old business administrator and is the probable presidential candidate for Fujimori’s right-wing party “Alliance for the Future”.

Courtesy of The Peruvian Times.